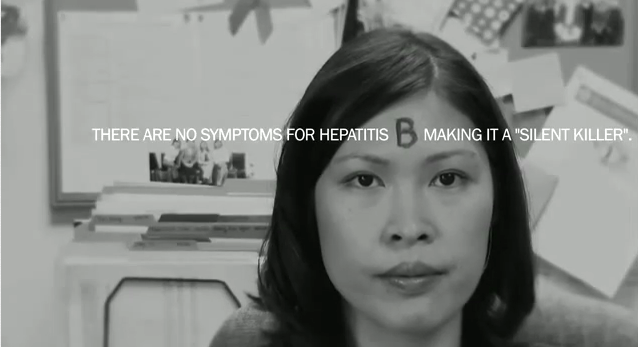

SEATTLE, WA — Every 30 to 45 seconds, someone in the world dies from complications related to the hepatitis B virus (HBV). In fact, 60 to 80 percent of liver cancer in the world is caused by hepatitis B. However, HBV is highly preventable through proper screening and vaccination, and even when contracted, it is very manageable through lifestyle adjustments and medication. Despite the Obama administration deeming viral hepatitis a “silent epidemic” in an official action plan for 2011, there is only a fraction of awareness compared to other diseases such as HIV.

According to the Stanford School of Medicine’s Asian Liver Center, over 2 million Americans have hepatitis B, two-thirds of them infected chronically (lifelong). Each year, 60,000 people become infected, and 6,000 die from complications related to the effects of hepatitis B.

According to the Stanford School of Medicine’s Asian Liver Center, over 2 million Americans have hepatitis B, two-thirds of them infected chronically (lifelong). Each year, 60,000 people become infected, and 6,000 die from complications related to the effects of hepatitis B.

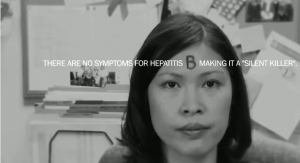

Two-thirds of carriers display no symptoms, making it difficult to become alert to and diagnose. It can be years before symptoms appear, and at that point, it may be too late for treatment. If symptoms do appear, they are commonly mistaken for influenza: loss of appetite, fever, headaches. Jaundice, which causes yellowing of the skin, may also be a sign of liver cancer.

Of the 2 million infected, half are of Asian-Pacific Islander (API) descent. The ratio of infected for Caucasians and African Americans is 1 in 1000. For people of API descent, it spikes to 1 in 10. These statistics, also collected by the Asian Liver Center, attest to a staggering health disparity.

Infection in regions of the world in which the virus is endemic, such as Southeast Asia and China, are usually through vertical transmission (mother to child). In the U.S., however, modes of infection are more commonly horizontal (person to person): through sexual contact or the sharing of needles. The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle discovered that in many cases, children have been infected by siblings from sharing toothbrushes and razors. Since Cambodians are relatively recent immigrants, the infection rate is more comparable to that of their homeland, where HBV is at epidemic levels..

Nandary Im, who wished not to be identified by his real name, is a 22-year-old college student at South Seattle Community College. During a routine physical exam, his doctor happened to ask if he was interested in a hepatitis B test. After consenting, Im found out that he is a carrier. “I hadn’t seen my doctor since I was younger. A couple days after a check-up, I get this message from him talking about I have hepatitis B. At the time, I wasn’t sure if I should’ve been shocked or not. I’ve heard of it but didn’t know exactly what it was. But I remember initially not being alarmed.”

Im’s response is typical. The Cambodian community has one of the lowest levels of awareness while being some of the most at risk for hepatitis B. “Even though I’m aware of being a carrier, I haven’t told many people, even my family. I’d like to ask my brothers if they’ve been tested, but I’m scared,” said Im. Out of a sample group of Cambodian Americans in Seattle, 56 percent had heard of HBV, 46 percent had received a blood test to determine if they were infected, and 35 percent were vaccinated against it. Less than 50 percent were aware of the different forms of transmission from one person to another.

According to a 2010 study by the Hutchinson Center, Cambodian Americans are 25 times more likely to have chronic hepatitis B infection than the average American. Hepatitis B is the second leading cause of liver cancer for Cambodian American men. Even so, health professionals have given little attention to the community. This is due to several factors, including the lack of health education and translated information about hepatitis B for Cambodians in the U.S.

Ninety percent of Cambodians speak Khmer at home, with nearly 50 percent living the below the poverty line making them one of the most culturally and economically isolated ethnic groups in America, according to published work by Dr. Victoria Taylor of the Hutchinson Center. As a result, the Cambodian community has a difficult time assimilating to “Western culture, institutions, and biomedical concepts of prevention.”

Following years of study, Dr. Carey Jackson, medical director of the International Medical Clinic of the University of Washington, concluded that even effective translations and interpretations of precise medical terms are “meaningless unless cultural concepts, common phrases and experiences” are thoroughly studied by interpreters and doctors in the field. Without more comprehensive research of Cambodian culture and customs, outreach groups found it difficult to effectively educate the community.

“There’s a stigma within affected communities to discuss [hepatitis B], and it’s a difficult disease to explain,” said Kim Nguyen, program coordinator for the Hepatitis B Coalition of Washington. “In addition, the act of translating information that is already complex to other languages causes loss in context.” For example, a study discovered that hepatitis B is understood to be several different illnesses or symptoms among Cambodian Americans. Chumnguh thleum (liver disease) and keut leoung (yellow skin disease) or jaundice were two designations given when asked about hepatitis B comprehension, among several others answers. This lack of consensus made translations of hepatitis B literature for the Cambodian community ineffective.

Traditional practices and cultural norms among the Cambodian immigrant population have also added obstacles to proper intervention. “I got the courage to tell my mom about it [hepatitis B]. She tells me how my uncle in Cambodia has fought it off by abstaining from alcohol and only eating fish and vegetables, and by seeing a witch doctor to prescribe other appropriate medication and lifestyle changes,” said Im. Before seeing a doctor for illnesses, research cited that Cambodians commonly resort to traditional remedies. This includes kos kchal, a dermabrasive treatment that involves using a coin to rub out and balance the “hot and cold levels” of the body, which many believe is necessary to stay healthy. When symptoms do appear, the average Cambodian immigrant is more likely to self-treat using these traditional methods, decreasing the chances for a proper diagnosis of hepatitis B.

Although the statistics paint a rather bleak picture, there is also promising momentum in the movement to further HBV awareness both locally and nationally. In Seattle, the Cambodian Community Coalition was established with the purpose of studying hepatitis B in the local community. A 2006 poll reported that there were improvements in women getting tested, 46 percent, compared to a 1999 poll that reported 38 percent. Although the polls indicate that much more work remains, the progress is encouraging.

“They were really polite when they came. They had Cambodians like us come explain what they were doing,” said Chho Collins, speaking about a visit from a Hutchinson field team. “They gave me a DVD with some actors playing out a scenario on how to spread awareness of hepatitis B amongst friends and family. I’m glad they’re out talking about this because it’s a problem in the community.”

In 2001, the Centers for Disease Control named May as Hepatitis Awareness Month. Last year, the Obama administration proclaimed July 28th to be World Hepatitis Day in order to help further the cause, releasing a presidential proclamation for greater awareness. The Asian Liver Center at Stanford University was founded in 1996 by Dr. Samuel So to investigate the high incidences of hepatitis B among Asian Americans. To this day, the center is one of the leaders in the fight against HBV and liver disease, providing some of the best efforts in outreach and education, advocacy, and research.

On May 9th, the Hepatitis B Coaliton of Washington hosted its annual HBV forum in the Holly Park neighborhood of south Seattle, home to one of the most diverse zip codes in America. Attendees included both local and nationally respected organizations, including the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Harborview Medical Center, and International Community Health Services, among many others. When asked what people should know about hepatitis B, Nguyen said, “There’s growing attention at the national level… always a need for health champions and advocates on the issue.”

***

What you can do: get tested. If you’re up for a physical exam, you’ll need to specifically request a blood test, as it is not typically administered. Get your family tested as well. If you test negative, get a vaccination. This will eliminate the chance that you’ll be ever infected. Currently, there are no cures for hepatitis B. But there are promising advancements of late. Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved several new medications that have proven more effective in treating the virus. In a February 2012 article with Voice of Asia, Dr. Taing Tek Hong of the Borland-Groover Clinic of Florida cited Pegasys, Baraclude, and Viread as some medicines for those with HBV.

Hepatitis B cannot be transmitted by air, food, water, or casual contact. Hepatitis B can be transmitted through blood, sexual contact, or sharing needles. Be aware that in a common household setti

ng, it can be spread through shared toothbrushes and razors.

For more information, see the following links.

http://ethnomed.org/patient-education/hepatitis/CambHepb.f4v/view

http://ethnomed.org/patient-education/hepatitis/Cambodian%20Hep%20B%20pamphlet%202010.pdf