By Jennifer Conrad

Kampot, Cambodia — For the last 20 years, the Kampot Traditional Music School has been working to preserve Cambodian music and dance. Many Cambodians overseas actively pursue Khmer arts as a way of keeping their heritage alive, understanding the country’s music and dance as part of their cultural identity. In a similar way within Cambodia, small organizations such as the music school in Kampot are striving to keep traditional arts from dying out. These efforts are now threatened by funding challenges that could force the school to close, a situation faced by many arts organizations across Cambodia—with the risk that unique art forms could be lost forever.

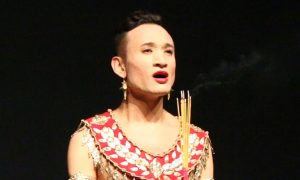

It is commonly believed that approximately 90 percent of Cambodia’s cultural artists and performers were killed during the Khmer Rouge era. With the number of masters of traditional art forms so decimated, many forms of music and dance that were once central to Cambodian life are now becoming marginalized. One of these is “yike” (pronounced “yee-kay”), a theatrical form of cultural expression once popular in rural areas, which the Kampot Traditional Music School aims to preserve. Through performances focusing on mythological stories, historical events, and messages about social cohesion, yike was traditionally used as a way to represent the issues faced by Cambodians in their daily lives—social messages that are still relevant to Cambodians around the world today.

Kampot yike is a unique form of this art, with music and movements specific to the province. However, in a region once well known for its many yike groups, the practice now lives on through only a handful of masters.

The school is lucky to count two remaining Kampot yike masters among their staff, both of whom have been performing yike for over 45 years. Mr. Khuon Bem, 60, and his wife, Mrs. Prum Savorn, learned the art from Savorn’s parents, who were well known within their village for their yike skills. The pair aim to keep this long history alive by offering training in Khmer traditional arts to the children in the area.

When asked why he thinks it is important to teach music and dance to the students, Bem said, “I want to transfer my knowledge and skills to the next generations so they are not wasted and lost.” The Kampot Traditional Music School offers him ample opportunity to share his expertise. It holds free afternoon classes for over 230 local students so that all children, regardless of income or background, have the opportunity to experience this part of their Khmer heritage.

With another 18 full-time students currently in residence, the school is also providing round-the-clock support to young Cambodians from disadvantaged backgrounds so they can learn the music and dance of their ancestors, often with a view to continuing this as a career.

Channika*, an 18-year-old student who has been with the school for 10 years, is currently one of the school’s star students and is the main actor in almost all of their dance performances. She said, “The school is not only important for me but also for those who have less access to education and art training… Without it, I would not be able to study, and I wish to be a classical dance trainer in the future.” A number of graduates have already gone on to become professional performers or teachers, helping to fulfill Bem’s wish for his knowledge to reach future generations.

However, resources for such activities are limited and the Kampot Traditional Music School is now facing closure as it struggles to make ends meet. Funding specifically for the arts is scarce and the competition is fierce—there are said to be only around 10 donor organizations for the arts focusing specifically on Asia.. These then face an overwhelming number of applications; for instance, 311 projects applied to Arts Network Asia in 2012, but just seven were awarded funds. This makes it increasingly difficult for small music and dance organizations to access consistent, long-term support.

The Season of Cambodia festival in New York this past spring garnered interest in Khmer traditional arts from those overseas, including Cambodian Americans wishing to embrace the cultural heritage this high-profile festival represented. But this interest appears to have been short-lived for many, as it has not yet had any financial impact on the small, local organizations back in Cambodia.

Funding for the Season of Cambodia came from a wide range of sources, including through American channels such as the New York Foundation for the Arts, which had no further effect in Cambodia once the festival finished. Large US-based foundations seem keen on strategic partnerships to promote international arts engagement and enhance American cultural institutions, but strengthening institutions overseas and supporting the next generation of traditional performers is less of a priority, given the temporary, event-based nature of that attention.

The closure of one small school may seem of little importance to the rest of the world. However, as well as the impact this will have on the lives of the children relying on this for their education, the shuttering of this small organization could also mark the beginning of the end for Kampot yike. Bem has said that without the school, he would be unable to continue teaching. “I have no place to provide training and no money to support the children… I have no plan, as I am old now.”

With masters of the art left unemployed, fewer students learning these skills and performances becoming rarer, the fate of this aspect of Khmer heritage is uncertain, maybe one day fading from memory. But just as the content of yike is meant to teach moral lessons, the preservation of this performance genre is also part of its legacy—a broader message about the value of tradition and art in connecting a community that is dispersed beyond its homeland.

Further information about the Kampot Traditional Music School can be found at http://www.kcdi-cambodia.com/.

*Note: Name changed to protect privacy.